by Paola Marabelli

Excerpt from:

Mastro Lisio: a life devoted to the Art of Silk, in Giuseppe Lisio, weaver of every colour, exhibition catalogue (Chieti, 14 November - 8 December 1998), Chieti 1998, pp. 15-23.

Photos and documents are from the Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio Historical Archive, Florence.

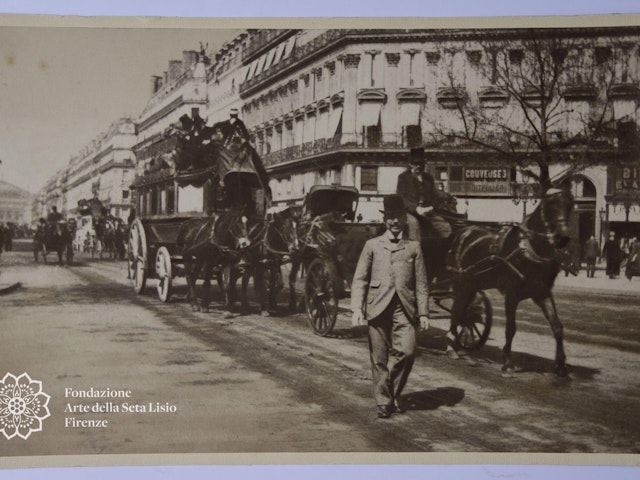

Right from the start, the seed of what later became a passion, a reason for living, can be attributed to chance, or perhaps to a natural inclination that in 1892 guided young Giuseppe Lisio at the age of twenty-two, to seek work in the famous "Luigi Osnago" silk factory in Milan. He got a job there as a sales rep and in 1900 was sent to set up the showcase to represent the factory at the Universal Exhibition.

"Osnago" formed part of the Italian textile section at this important event where it was a leading exhibitor with 34 different fabrics including damasks, lamé velvets, brocatelle and embroidery characterised by "decorative repertoires all oriented towards historical styles of past eras, except for a green and corn-yellow lampas, in Liberty style.

Therefore, it was in this well-established Milanese company specialised in upholstery fabrics that Lisio cut his teeth, as we say, and began to cultivate his interest in the artistic reproduction of fabrics and the search for a quality production to play up against current use.

Despite the somewhat fragmentary documentation in the Foundation's possession, we can still outline the events marking Lisio's industrious life and understand his ardent desire to create a prestigious business. It is possible to immediately observe Giuseppe’s resourcefulness in his writings when in 1905 he "conceived and created" the company "Tessiture Riunite".

On 18 February 1905, "Tessiture Riunite" was founded in Milan, with a managing partner, Costantino, son of Luigi Corsini, and other limited partners, including Lisio himself. Article 2 of the Articles of Association states that "The Company’s purpose is the wholesale and retail trade of fabrics for furniture, upholstery in general, ladies' fabrics and similar items".

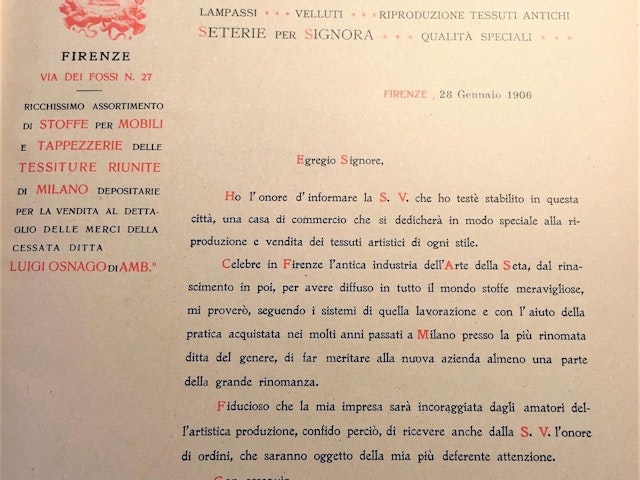

An indication in another paper clarifies this matter by stating that "Tessiture Riunite" consisted of "repositories for the retail sale of merchandise of the former company "Luigi Osnago di Ambrogio". Therefore, after "Osnago” closed down, Lisio promoted and participated in this company, later liquidated on November 22, 1923, in anticipation of a far more important step.

The document from which we extracted the previous step in fact constitutes certification of the beginning of Lisio’s independent activity.

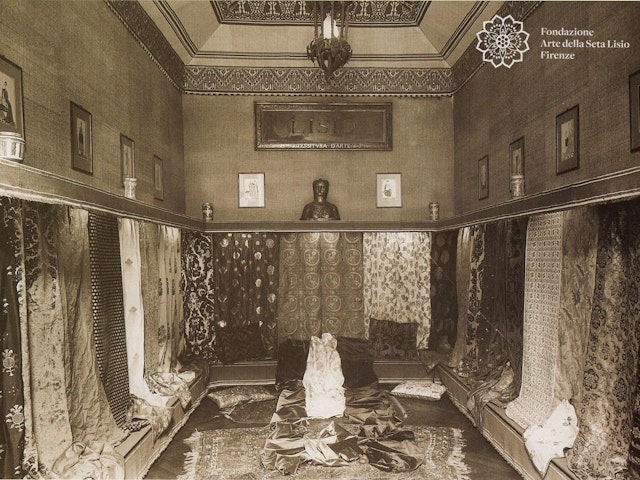

This was the presentation, dated 28 January 1906, of the inauguration of the Florentine headquarters in Via dei Fossi 27, denominated "a trading house dedicated in a special way to the reproduction and sale of every style of artistic fabrics" where one could find "a very rich assortment of fabrics for furniture and upholstery of Tessiture Riunite of Milan...".

During his Milanese beginnings in the textile sector, Giuseppe Lisio travelled extensively and became particularly fond of Florence.

Following are his own words illustrating those beginnings:

"Visiting Florence and most interested in everything that could add prestige to the Italian silk production, I was struck by the memory of one of its major arts, perhaps the best, "the Art of Silk"... At the beginning of 1906, enthusiastic about my research on this Art, I decided to move to Florence and enrolled at the local Chamber of Commerce as a silk maker, I started a very intense business on my own, and my main intention, if nothing else, was to remind new generations of the splendour of that very noble Art...

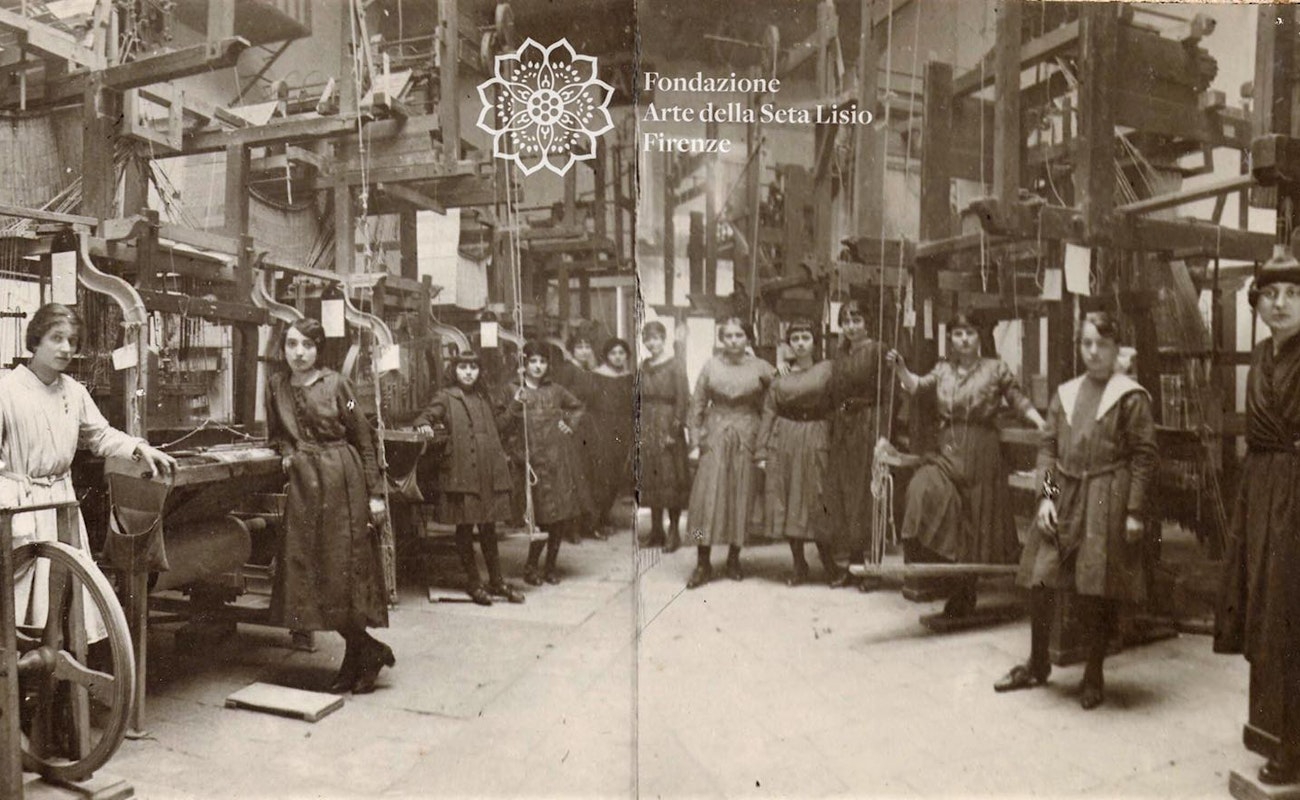

In those years in Florence the art of weaving was completely dead, because, after much research, I was hardly able to find any old ladies who had used the shuttle in their youth, I remember the most skilful, Adele Gambini, who, assisted by another good weaver I had summoned in Florence, managed to teach several young women how to weave on the ancient loom.

The first designs, although classic, were simple and faithfully reproduced, and as it was necessary to make them known immediately, I decided to open a workshop called Arte della Seta.”

Thus, his first shop and manufactory opened in Via dei Fossi in the Oltrarno district. Then, in 1911, he rented premises from the Municipality of Florence on the ground floor of the so-called "Case degli Alighieri", in which he renovated the home of a fourteenth-century Florentine silk manufacturer where he displayed and sold his fabrics.

For this new initiative, Lisio was praised and acclaimed both for the setting created with the reproduction of antique furniture and utensils, and for the style in representing his artefacts, but he was also criticised by those who unwittingly perceived a desecration "of the objects belonging to the poet". Tired of the controversy "I decided to forego the remaining lease period and left that house that had already been such a burden on my budget". It was December 1, 1914.

Lisio's fine fabrics soon became known for their beauty and quality and numerous orders poured in not only from the Florentine, aristocratic and public circles, but also from the rest of Italy and the world.

In 1911 several examples were displayed in the Tuscan pavilion of the Mostra delle Regioni in Rome and the same year he opened the shop in Rome, Via Sistina, 86.

Continuing our research, we can see how in this period Lisio focused his attention on the capital and tried to give substance to an important project. From his notes in two "memorials", one to Corrado Ricci, Director General of Antiquities and Arts and the other to the Mayor of Rome, dated 1917-1918, we learn how he wanted "to establish a School of Silk Art in Rome including weaving and also dyeing in order to reproduce classical fabrics from the remotest periods to more recent times".

Describing his experience in the field, he declared:

"having set up a school in Florence 10 years earlier for weaving brocades, brocatelle and general decorative fabrics, I want to move to Rome, the most propitious place for the renewed expansion of an art that is already ours, since everything given which divides returns to us".

Two aspects of this Roman affair are interesting to note: the first concerns the idea of transferring an already launched activity to Rome, where it would have found more incentives given the presence

“of the Court, the Papacy and the Ambassadors at the Quirinale near the Vatican (whose work of diffusion of Italian works is greater than is commonly believed), a very special and almost exclusive site of museums containing classical fabrics, some of which date back to the earliest antiquity (such as the Vatican and Kircherian Museums)".

The second concerns the fact that, while attentive to the economic-commercial aspect, he emphasised the need for a School, believing firmly in the necessity and value of the rebirth of a very ancient Art that must not be lost in oblivion, and in continuity for a future able to equal the splendours of the past.

He founded these beliefs on studies and research that marked his entire life.

In fact, there are numerous notes on the Silk Art history taken from the publications of the time, some of which had been purchased, forming a small library. In addition to studying texts on textile techniques, he built up an authentic photographic archive of fabrics and general artworks, from which he drew inspiration for his creations.

However, Lisio never carried out his Roman project and

“on returning to Florence, I transferred my workshop to other larger premises and by increasing the number of looms and training new workers, I was even more aware of the need to produce as much as possible to valorise that Art, the traditions of which were so important to me. Success followed my work due to the fact that, never receiving complaints, or rather, avoiding them, my fabrics became more and more widespread, reaching, dare I say, nearly all the European Courts”.

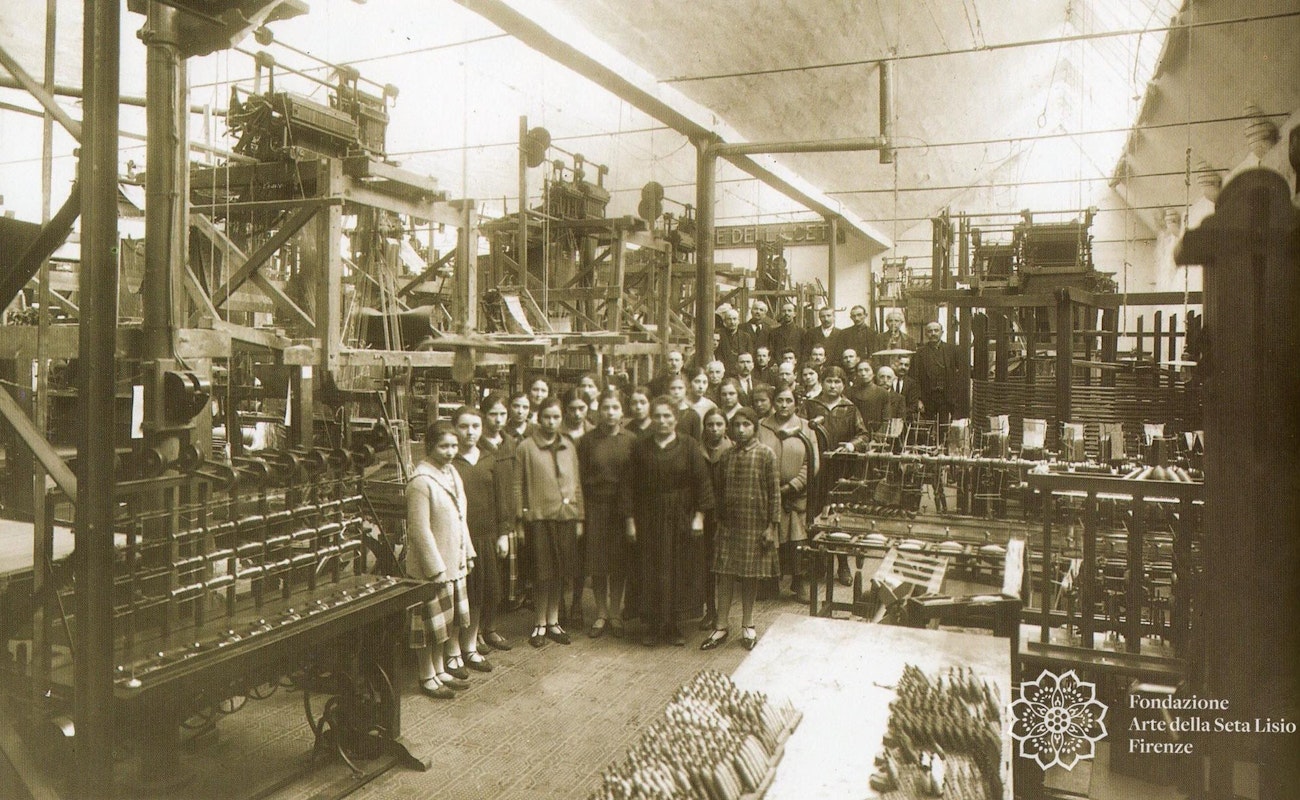

While the clientele gradually increased, as did the commissions, the Florentine workshop became so insufficient that Lisio decided to move the weaving to Milan, where he would be able to boost production more.

As indicated in several newspaper articles, 1924 saw the inauguration of the shop in Palazzo Borromeo, Via Manzoni 41, and the school-workshop in Via Vigentina. An article by Ferdinando Paolieri in the Florentine "La Nazione" also celebrated the work of the "animated and very ingenious founder of the Arte della Seta", and reprimanding the city of Florence, declared:

"after having done all he could to infuse new lymph, he was forced to resort to industrious Milan to develop this art increasingly more, something hardly possible to achieve in Florence with the same degree of intensity, therefore today in Milan he can make even the most complicated velvets from the best Florentine era with a number of looms that in Florence would have been impossible to beat".

It is interesting to note, as emerges from this article, how despite having moved his manufactory, Lisio considered his business “essentially Florentine”.

Great industriousness characterised the life of Lisio, who, animated by an unceasing fervour of initiatives, decided to erect a building in Milan to serve both as a home for his family and the site of his manufactory.

Dated 6 March 1929 is the ”Quotation for the construction of a house and annexed workshop to be built in Milan, in Piazzale Libia, corner of Via Silio Italico".

After several years, since the noise of the looms could not be reconciled with the closeness of the home, the manufactory was moved to Via Friuli 6 where it remained until closing at the end of the 1950s.

Consensus surrounding the work of “Mastro Lisio” was unanimous, both with connoisseurs of fine fabrics and the clientele, many of whom expressed esteem and consideration in letters passed down to us.

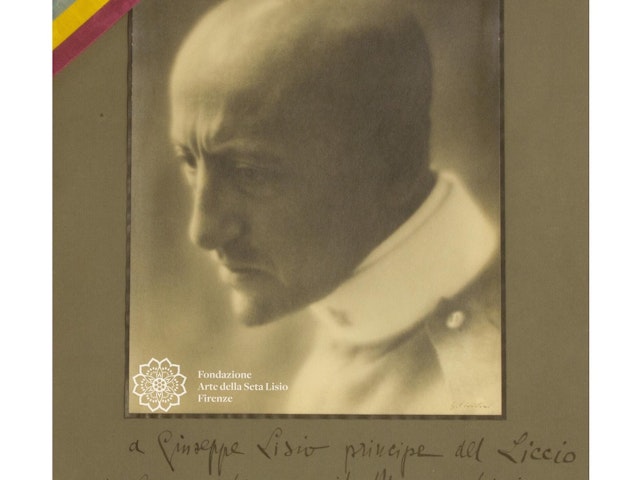

His most consistent correspondence was with Gabriele d'Annunzio from 7 April 1925 until 28 February 1938, the day before the Poet’s death.

The consonance of these two spirits from Abruzzo is evident in the letters, nourished by words of appreciation, sincere devotion and consideration towards each other in a mutually gratifying relationship.

The rich correspondence between Lisio and D'Annunzio's wife, Maria Hardouin, Duchess of Wales, is also pervaded by a strong sense of admiration, but above all, a heartfelt friendship which in Donna Maria's letters revealed a deep sadness due to her difficult position.

With Luisa Baccara, Venetian pianist and d'Annunzio's last companion, the cordial exchanges are centred on requests for fabrics for furnishings and clothing on behalf of the Commander or for personal use, as well as later requests for creating the folders to contain D'Annunzio’s manuscripts donated by Luisa to the Fondazione del Vittoriale.

There are also letters from Gardone Riviera signed by architect Gian Carlo Maroni, Superintendent of the Vittoriale degli Italiani, who maintained an intense correspondence with Lisio containing commissions for fabrics interspersed with expressions of deep friendship, consolidated by the shared memory of the beloved Commander, D’Annunzio.

From a series of postcards exchanging new year’s greetings, another famous name stands out, that of Francesco Paolo Michetti, a great friend of D'Annunzio who mourned his death intensely and appreciated Lisio sympathy in participating in his grief.

There are other illustrious names, such as that of the Borromeo family, for whom, in addition to the correspondence, we also have Lisio's drawings for the decoration of a hall transformed into a chapel on occasion of the wedding of Donna Laura Emilia Borromeo Arese, daughter of Giberto Borromeo, to Count Carlo Borromeo d'Adda, son of Count Febo.

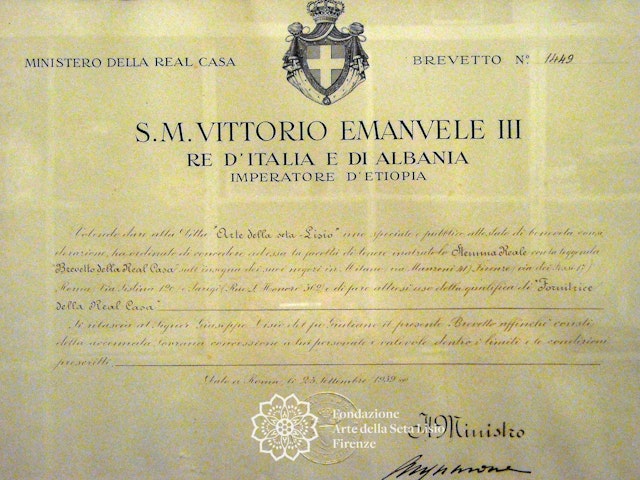

The House of Savoy also made use of "Lisian art", as can be seen from a brief epistolary, and above all from the certificate as "Supplier to the Royal Household", issued on 23 September 1939.

Despite receiving important plaudits and orders, Giuseppe Lisio began to be tired and above all, disheartened. The general economic and commercial difficulties and the lack of more reliable collaborators were undermining the vitality and passion that had always sustained him.

The short epistolary with Erminia Favi is enlightening in this regard. On 13 May 1934 he wrote:

"....I'm slowly deciding to withdraw at least from the commercial side and I think I'm ready, so much so that here [in Milan] I'm making the inventory behind closed doors and it's also likely that this closure will be final if for the new season I don't find the right person to carry on ...".

Favi replied with a heart-warming and encouraging letter:

"...True, we are going through sad times, but I wonder how it can be possible for a creation like yours not to possess enough vitality itself to overcome and win! True, you have too much weight on your shoulders and spending your life rushing between Milan - Florence - Rome - Paris is taxing, not to mention that it will not be physically possible to take care of everything...".

In replying to her on May 23, 1934, while expressing appreciation for her comfort and friendship, Lisio declared his diffidence:

“…You have understood me exactly, or at least my situation, as perhaps no one else has. I'm not tired, I'm disheartened. You wonder ‘how a creation’ like mine could perhaps not possess enough vitality to overcome and win’. I still certainly hope so. More vitality, however, than what I am able to instil, I am no longer able to, I’m almost exhausted. But what's the use? I've had six employees working in the warehouse alone for many years, and this month I've had to lay them all off because I cannot be held liable for their lack of cooperation. So how could I last on my own? See what's happening in Florence after my departure, crisis, yes. But there's something else too. And believe me, I'm not hard to please and it's not true that I’m difficult, I only demand what is necessary to demand…”.

That Lisio really intended to retire is confirmed in the "Conventions" and "Assignments" dated 1936 and 1939, which were drafted several times, and which indicate inter alia:

"At the end of this year 1936, the Lisio Company celebrated thirty years of artistic-industrial activity, during which it was able, with the production of its art fabrics, to resume the interrupted ancient "art of silk" of Florence, where the same company originated, establishing itself with a supremacy that it still holds today.

Its Owner, who has decided to withdraw from the commercial part of the company to devote himself exclusively to his own creations, proposes entrusting the headquarters in Milan to a subject capable of running the company according to the criteria and characteristics that have distinguished it until now; initially under autonomous management, before arriving at final closure".

From this documentation it appears that he had made preliminary agreements with F.lli Fumagalli, and later with Cristiano Schmid, and that on 31 March 1939, he had defined the values of the goods in stock as "Stock and Warehouse fabrics" and the methods of payment, up to the sale of the Factory.

But this transfer never took place, Lisio continued to fight for his business, and despite being aware of the need to make a significant change in his activity he drew up a "technical-financial plan" submitted on June 16, 1941 to the Marquis Advocate Giuseppe dè Capitani d'Arzago, Minister of State, who was involved in all works of a national interest. In it Lisio proposed the establishment of a Foundation or Society entitled "Arte della Seta" in order to develop artistic production and export.

The "rebirth" and "continuity” values of the ancient Italian silk art, the true cornerstones of Giuseppe Lisio's existence, dovetailed with the ideas and interests of the widespread national production at this specific time in history.

Especially worth mentioning, Architect Gio Ponti who demonstrated profound esteem for Lisio and really wanted him to participate in the 7th Triennale di Milano. On 7 January 1939 he wrote:

"Illustrious Lisio, at the end of March 1940 XVIII, the VII Triennale opens. Your participation must be organised. Can we meet?"

And on 1 February 1940 he wrote:

“It is extremely important for me that you attend this gathering of the noblest national forces of this era. Your absence would cause me great sadness”.

Their contacts continued with subsequent letters in which Lisio approved Ponti’s "national campaign" undertaken in favour of our art productions that form "the powerful force of export ", while Gio Ponti, on 13 June 1942, proposed establishing the Giuseppe Lisio Prize for fabric designs at the triennial into which prizes offered by art industries flowed.

The Lisio’s vicissitudes in later months can be followed through letters to the “Hermitage” of Rapallo from his nephew Teodoro Olivieri who looked after the “Lisio – Tessuti d’Arte” interests in Milan. On 18 January 1943, Teodoro wrote to his uncle that Corbetta, a newly hired worker, had started using his loom at Silio Italico and that:

“concerning our production, relevant provisions are still in progress and are expected at any moment. I have also appointed a trusted person in Rome who, given his position can, inquire with the competent Ministry, and keep me informed".

Then on 23 January he wrote:

"the permit for closure of the Milan office expires in May, the one in Florence does not expire and can be either closed or reopened whenever you want since the license is only in deposit without a fixed term. The one in Rome was recently renewed for a period of three months. The factory continues its work with the six looms, including Corbetta at S. Italico, where everything is running smoothly".

We are not currently able to define in detail the events relating to the closure of the factories which are mentioned in another two letters. In fact, it is with his friend Gio Ponti that the correspondence of Giuseppe Lisio held by the Fondazione ends.

On 16 March 1943 he wrote to the Milanese architect from Rapallo saying:

"I've thought of you many times, especially after the accident in my house in Piazzale Libia, which is now in need of urgent repair to avoid further damage... Tomorrow I'm going to Rome and when I return I hope to have the pleasure of seeing you here at my "Hermitage" where I'm taking shelter, so we can talk about the disappearing Art.

His friend promptly replied on 24 January asking for explanations about the closure of Milan and inquiring about Florence. He also enclosed a letter sent to him by Fede Cheti:

"Dear Ponti, I see Lisio has closed. Why? I’m so sorry. Such a profoundly Italian tradition and beauty must not be interrupted or even momentarily suspended".

In his last letter dated 2 April 1943, Lisio wrote:

"Dear Ponti, after a stay in Rome and Florence, back here I find your dear letter dated the 24th, with enclosed that of very kind Fede Cheti. What can I tell you? For me it is a great comfort to read certain expressions at such a tragic time for all the Arts, especially mine, to which I have dedicated my whole life, to keep alive, at least the memory, of a very Italian tradition, which I believe will soon disappear. And since few people know its history, consider how pleased I am that said Art is so nobly appreciated, both by you and by the prolific and fervent artist you are introducing.

I’ve had to close all the factories, including Paris. Why? Because I can't resign myself to producing fabrics according to the proscriptions issued, so I’ve stopped the sale of Art Fabrics. Practical steps are being taken now to get both production and sales reactivated in the right way before a valuable workforce disappears. This is what you can tell dear Fede Cheti, whom I would love to meet, but since the accident in the building created precisely for the Arte della Seta in Piazzale Libia, I don’t have the courage to come to Milan to see the damage. Anyway, I hope we can come back soon, and I'll tell you my best impressions, about your very interesting article "LA CASA MODERNA".

As we can read, also between the lines, Giuseppe Lisio perhaps appears to be somewhat fatigued, but always active, alert and lively in spirit, devoted to "his Art” up until the very end.

Giuseppe Lisio died on 16 April 1943.

by Paola Marabelli

Excerpt from:

Mastro Lisio: a life devoted to the Art of Silk, in Giuseppe Lisio, weaver of every colour, exhibition catalogue (Chieti, 14 November - 8 December 1998), Chieti 1998, pp. 15-23.

Fidalma Lisio and the Art of Silk

A combative woman with a firm will to preserve and hand down the Art of Silk. A "mission" that brought the Giuseppe Lisio's manufactory in the 3rd Millennium.